Historic Designed Landscapes Project

The content on this page was originally published as a PDF titled Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, Historic Designed Landscapes Project: Summary Report. The report was created in 2012 by:

Consultants

Peter McGowan Associates, Landscape Architects and Heritage Management Consultants

6 Duncan Street, Edinburgh EH9 1SZ • 0131 662 1313 • pma@ednet.co.uk

and Christopher Dingwall, Garden Historian

The report has been published here in HTML to improve accessibility for all users. If you would prefer to view the original PDF document, or if you would like to view more detail for each site listed in this report, please contact us.

This report is intended for reference by developers in the pre-application stage if a development is proposed on a designed landscape.

Contents

1 Introduction

2 Background

3 Methodology

4 Limitations

5 Distribution and setting of sites

6 Size of sites

7 Types of site and main uses

8 Main periods of development

9 Features and facilities

10 Management issues

10.1 Conservation and management of planted features

10.2 Visual issues

10.3 Division and dereliction

10.4 Building use and built features

10.5 Other conservation and access issues

10.6 Issues in relation to development, development pressures generally

11 Management recommendations – five potential project areas and priorities for designed landscape conservation

12 Conclusion

Appendix 1

List of sites

Appendix 1, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, a summary history of its designed landscapes

List of sites as shown in map, with reference number

06 Arden House

08 Ardgartan

05 Ardvorlich

07 Auchendennan

09 Balloch Castle *

35 Benmore *

11 Bennachra

01 Boturich Castle

38 Buchanan Castle *

13 Caldarvan

14 Cameron House

10 Camstradden

26 Dalnair (aka Endrickbank)

03 Drimsynie

02 Drumquhassle, Park of

12 Duchray Castle

24 Edinample

16 Edinchip

27 Finnich Malise

17 Gart

25 Gartmore

15 Glenfinart (aka Dalrymple)

21 Glenloin House

33 Inchmahome *

18 Inverstrossachs

36 Kinnell

32 Leny House

31 Lomond Castle (aka Auchenheglish)

37 Rednock *

30 Roman Camp *

04 Ross Priory *

34 Rossdhu *

39 Shannochill

29 Stronvar

20 Stuckgowan

23 Tigh Mor

22 Wards

19 Westerton

28 Woodbank

(asterisk refers to Inventory sites)

1 Introduction

In 2009 Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA or NPA) engaged consultants to prepare a register of designed landscapes within the National Park. The aim of the project has been to identify individual sites, to describe their features and extent, to assess their condition and to make recommendations on future management. It is the intention of the NPA to use this information within the planning process, to make informed decisions on development proposals, and to direct and prioritise available funding towards appropriate management, and the conservation and/or restoration of landscape features.

This report summarises the findings and issues arising from the survey of sites.

The main body of information from the survey is to be found in individual reports on the thirty-nine sites selected for inclusion in the register. In addition, an advisory note giving management guidance for landowners and land managers has been prepared.

These documents have been prepared by the appointed consultants – Peter McGowan Associates, landscape architects, jointly with Christopher Dingwall, garden historian, and with Ironside Farrar providing GIS mapping services.

2 Background

Gardens and designed landscapes can be defined as grounds that are consciously laid out for artistic effect. They generally comprise parkland, woodland, water features and formal garden elements, and often provide the setting for important buildings. Some may include features of archaeological and/or scientific interest. These designed landscapes make an important contribution to landscape character, and to people’s experience of the National Park, whether as residents or visitors. Particularly in the more settled and cultivated parts of the park, features such as policy woodlands, specimen trees, gate lodges and estate walls make an important contribution to the scenic and historic character of the area.

The Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland, compiled and maintained by Historic Scotland for Scottish Ministers under the terms of the Historic Environment (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2011, is a list of nationally important sites which meet the criteria set out in paragraphs 2.63-2.75 and Annex 5 of the Scottish Historic Environment Policy December 2011 (SHEP 2011). The Inventory was first compiled in the 1980s and published in 1987, when it included details of 275 sites. Following the publication of three supplementary volumes covering the Lothians, Fife and Highlands & Islands, between 2001 and 2005, the decision was taken to make the Inventory a digital record and to publish further additions on-line. Following a resurvey, there are currently 386 sites included in the Inventory, of which seven lie wholly or partly within the National Park.

Although there is no primary legislation offering statutory protection to Inventory sites, inclusion in the list means that a site receives recognition and a degree of protection through the planning system, with local authorities required to include appropriate policies for their safeguarding in strategic and local development plans. Under the terms of the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2008, local authorities are required to consult Scottish Ministers on ‘development which may affect a historic garden or designed landscape’. Historic Scotland’s views are therefore expected to be a material consideration in the planning authority’s determination of such applications.

In addition to those sites included in the Inventory, however, there are many other designed landscapes throughout Scotland that, though they may not meet the criteria for national importance, nonetheless make a major contribution to the local historic environment and landscape character. Indeed, the Garden History Society has estimated that the Inventory represents less than 20% of the significant historic gardens and designed landscapes nationally. Recognition is given to these sites in paragraph 3.79 of SHEP 2011, which encourages local authorities ‘to develop policies within their development plans for the identification and future management of such non-Inventory sites in their areas’ . This statement is underpinned by the Scottish Government’s advice note SPP23, Planning and the Historic Environment. This, too, acknowledges the importance of non-Inventory sites by pointing out that ‘there is a range of other non-designated … gardens and designed landscapes … which do not have statutory protection. These, however, are an important part of Scotland’s heritage, and Government policy is to protect and preserve these resources through the planning process’ . In formulating policy the NPA also has to take account of paragraph 1(a) of the National Parks (Scotland) Act 2000, which makes it the duty of the authority ‘to conserve and enhance the natural and cultural heritage of the area’ .

The above-mentioned policies and recommendations have been translated at the local level through the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Local Plan, adopted in December 2011. In this plan Policy ENV24, Historic Gardens and Designed Landscapes states that ‘development affecting historic gardens and designed landscapes shall protect, conserve and enhance such places, and shall not impact adversely on their character, important views to, from or within them or their wider setting’ , with the accompanying observation that ‘even where there are only remnants of the original historic gardens and designed landscape, these places continue to make a contribution to the Park’s special qualities through their planned composition’.

The NPA aims to achieve this in part through the development and implementation of management plans, which will be made a condition of planning permission granted for development within historic gardens and designed landscapes. The NPA also intends to promote other initiatives for the renovation of designed landscapes within the park.

3 Methodology

The project involved a number of stages including selection of sites, research, site visits and reporting as follows. The budget for the project was spread over three financial years between 2009 and 2012 and this has determined, to an extent, the process adopted and the programming of the stages.

Stage 1 – desk-based research, using a variety of mostly secondary sources, leading to an initial list of fifty-two sites (including Inventory sites, and a few sites just outside the park boundary but with visual links to the park) with a brief description of each. From this initial list thirty-eight sites were chosen by the NPA for closer study, to which number one further site was added part-way through the project.

Stage 2 – further research in greater depth into the chosen sites, using selected maps, published and on-line sources to produce a historical account of each site and to assist in the planning of site visits. The information sources used are listed in the bibliography at the end of each site report.

Stages 1 and 2 were undertaken in the winter of 2009-10.

Stage 3 – site visits to assess each of the chosen sites, to record its features in notes and photographs, and assess its current condition.

Stage 4 – write up of a survey report for each site, incorporating previous historical account, and preparation of a plan for each site showing its location, extent and features in GIS.

Visits and the writing of the site reports were spread over two years, half undertaken in 2010-11 and the other half in 2011-12; the survey reports note the date of visit.

Stage 5 – summary report and advisory note of management guidance.

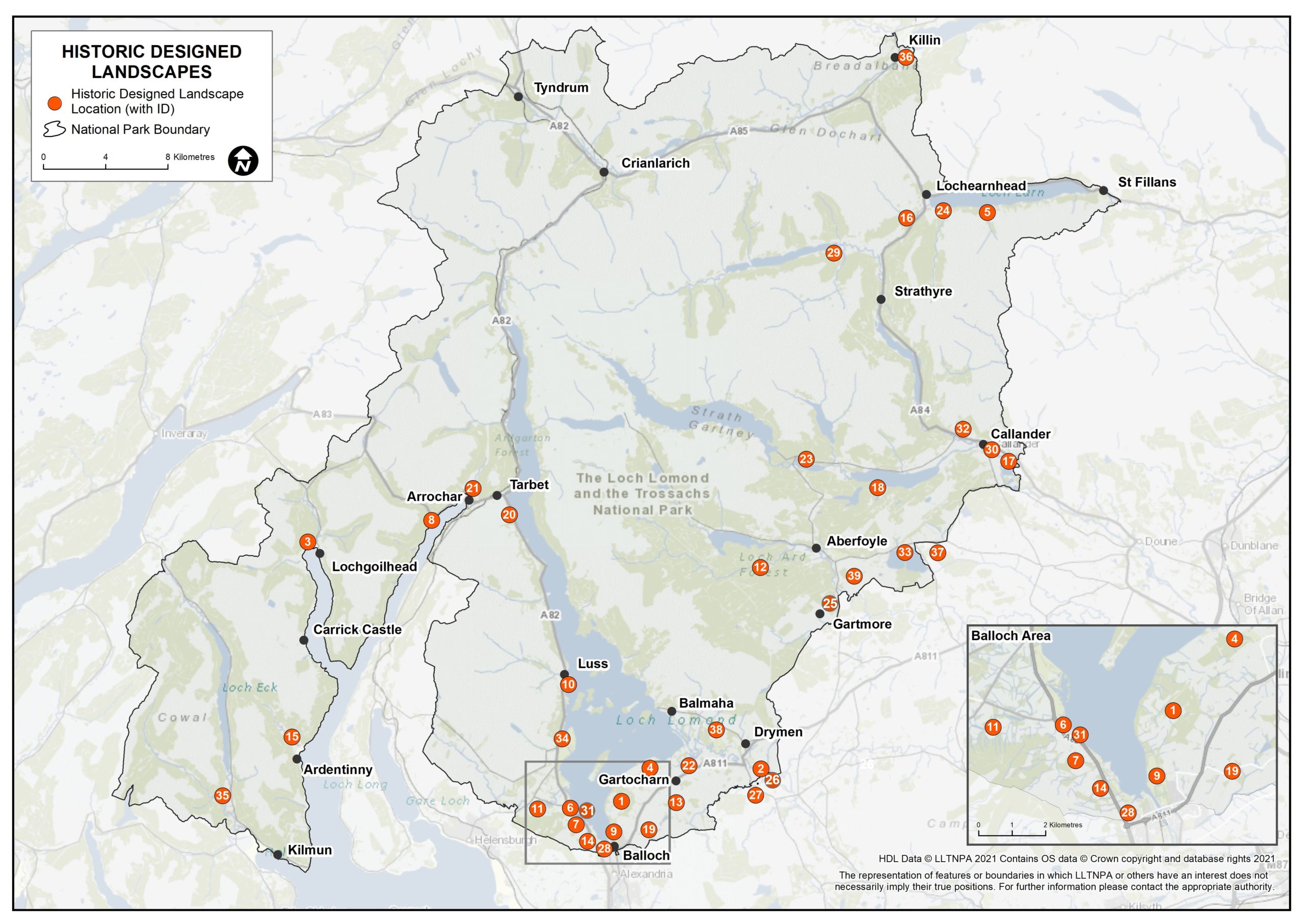

The locations of the thirty-nine sites are shown on Figure 1 at the back of this report.

A Historical Summary was produced in March 2010 and is included in the back of this report as Appendix 1.

4 Limitations

The individual site reports are intended to serve as a useful point of reference for the NPA, for other organisations, and for members of the public with an interest in cultural landscapes. The reports, however, are not in-depth studies, as in most cases more detailed accounts could be compiled, based on further research, particularly of primary or unpublished sources, and by more thorough field investigation. The site plans in the reports are similarly limited in their scope, relying to a large extent on existing information recorded on Ordnance Survey maps. In most cases no plotting of new information has been possible, owing to the limited time available. It should be noted that site boundaries on the plans are based on map analysis and field observation, and are not intended to show the historic extent of estates, or the limits of past or present ownership.

Although the register adds substantially to available records of the number and extent of designed landscapes within the National Park, and to an understanding of the contribution that these landscapes make to the scenic quality of the park, the resulting list of sites should not be regarded as comprehensive. While the primary focus of this survey has been on larger sites, there are many other smaller places where woods and planting contribute significantly to the local scenery. Also, while they are recognised as having an important part to play in determining the character of the National Park, there are certain types of designed landscape which have been deliberately excluded from the survey – most notably those to do with large scale forestation, or associated with power generation and water catchment.

Image: Cameron House and Auchterderran designed landscapes seen across the south end of Loch Lomond from Balloch Country Park

Image: Stronvar seen across Loch Voil

5 Distribution and setting of sites

(see Location of Sites plan – available on request)

As may be expected given its size and accessibility, a large proportion of the sites are located around the shores of the Loch Lomond, with ten of them having a loch-shore boundary and excellent views of the loch that are an important aspect of their composition. The majority of these are concentrated on the south-west part of loch shore, adjoining each other, and are the main determinant of man-made landscape character in this area. Nine more sites are located in similarly fine settings on the edges of other lochs – both sea lochs and freshwater lochs – including lochs Goil, Long, Achray, Venacher, Voil and Earn, and one (Inchmahome) on an island in the Lake of Menteith.

Away from the lochs, several sites still have a watery outlook but lie next to rivers, such as Kinnell on the bank of the river Dochart, Roman Camp and Gart on the river Teith, and Buchanan and Dalnair related to the Endrick Water.

A significant proportion of sites lies in what may be termed as the lowland part of the National Park, on the south shore of Loch Lomond and to the south of there. About a dozen sites are located in this zone although many of these still have distant views of high hills. All the rest are in the highland parts of the park and inevitably views of hills as well as water bodies play an important part in their setting and contribute to their character.

Given the few towns within the National Park, it is unsurprising that only a few sites are related to the towns in or adjoining the park. The few include Balloch Castle outside Balloch and Leny and Roman Camp on the edge of Callander.

The important thing about the natural features of the topographic setting of sites is that they are the dominant and most significant features of these ‘designed landscapes’. These natural features are the reason the designed landscapes are here and are the canvas on which man has overlaid built and planted features to improve the landscape productively and enhance it aesthetically.

All of the sites lie within the national park with the exception of Rednock, on the east shore of Lake of Menteith. This Inventory site has been included due to its visibility from the park and the approach road to the park.

6 Size of sites

Sites range greatly in size from the smallest – Glenloin 5ha, Roman Camp 8ha and Lomond castle 8ha – to the largest – Buchanan Castle 1,735ha – although these places are not typical. The rest of the sites are in the range of 30ha to 450ha.

Image: Roman Camp, one of the smallest sites, and river Teith.

No particular lower size limit was made when selecting potential sites, although sites have to be of a particular scale or presence in the wider landscape. The three small places were included due to the national importance of one (Roman Camp is an Inventory site) and the high impact of all three in the local landscape.

Although no systematic comparison has been done with sites nationally, it would appear that the designed landscapes generally within the park are modest in scale compared to other areas nationally, perhaps on account of the topographic difficulties of steep ground limiting the extent of landscape ‘improvements’. The fact that many sites were created, in effect, as ‘second homes’ may also have been a factor.

7 Types of site and main uses

When we use the term ‘designed landscapes’ we think mainly of country houses and their policies or estate landscapes, and it is this type of site that predominates in the national park, albeit that the use of the site has changed in some cases. A large proportion of these – twenty-two sites – remain in this type of use with the house still occupied by the owner or in a few cases by tenants.

However, in many cases the full extent of the designed landscape is not in the same ownership as the house. It is estimated that twenty-three sites are now in divided ownership, with the many issues of lack of coordinated management that often results. At five sites the house is ruinous or has been demolished. At least two houses have been sub-divided into flats (at least two others include holiday apartments with owner occupation) and four are in institutional use.

Two sites were originally developed as hotels or have been in this use for much of their lives (Tigh Mor and Roman Camp) and a further four are now used as hotels or one as a youth hostel. Caravan sites occupy part of six sites and four have chalet development within their grounds.

Image: Former Trossachs hotel, now An Tigh Mor Trosachs Holiday Property Bond time-share development, in its landscape setting.

The grounds of country houses have often been seen as potential sites for parkland golf courses, either club-based (Rossdhu, Ross Priory, Buchanan) or part of larger leisure developments with hotel, chalets and indoor leisure facilities (Drimsynie, Cameron House). Only two are in pubic ownership – Balloch Country Park (West Dunbartonshire Council) and Benmore (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh).

8 Main periods of development

Scots baronial Auchterderran house

New design features in walled garden at Ross Priory

Edinample, late 16th century tower house

The great majority of the designed landscapes were created in the 19th century, although in some cases incorporating features from earlier layouts, with 19th century houses as their focus – thirty of the thirty-nine houses (including here Tigh Mor and houses now standing ruins) – are of this period. Of these fifteen are Scots baronial in style and six in classical style (with another 18th century classical). Others are gothic or in traditional Scots in design.

Two sites have late-16th century tower houses as their focus (Duchray, Edinample) and a third has a 16th century house added to in the 19th century (Leny). Three have 18th century houses at their core. Two places are the sites of 20th century houses.

At almost all sites the landscape has been improved and redesigned during the 19th century in the ‘natural’ style of the period, regardless of the original period of the house, so it is of particular interest that one 18th century house – Kinnell – retains a formal rectilinear layout and features (straight drives, gateways) typical of the earlier 18th century.

For more detail on the historical development of the sites see Appendix 1, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, a summary history of its designed landscapes.

9 Features and facilities

All the designed landscapes have tree belts and woodlands to a greater of lesser degree and this aspect of layout is the most important in their contribution to the wider landscape and local scenery. Parkland is less prevalent, with twentyfour sites having this feature. Twenty-one sites have gardens or tree collections, although many of these are small in scale and private. Foremost among the gardens and plant collections is Benmore, with Balloch Castle, Ross Priory and Rossdhu also significant.

Walled or kitchen gardens survive at twenty-seven sites, of which fifteen are cultivated in whole or in part, in traditional productive use or as ornamental gardens, or a combination of the two – probably a higher proportion than the national average. The other thirteen walled gardens are either grassed over or in some cases derelict.

Estate buildings including gate-lodges, stables courtyards, cottages, icehouses and follies remain at twenty-nine sites, although they vary greatly in their condition (see below).

Image: Hillside parkland, the finest in the national park, at Leny, Callander.

10 Management issues

The sites in the survey cover a great range of condition from well preserved estate landscapes under traditional management to places in divided ownership and areas of dereliction, and from sites that have been renewed wholesale with major investment and uses to others with piecemeal development and insensitive change. Fifteen sites can be considered overall to be well-preserved (even though they may have less well maintained areas), while thirteen may be considered to have significant neglected or derelict areas, including destroyed features in some cases.

Fortunately the number of places where the landscape has been irreversibly altered or had intrusive development are few and, although the following list of issues may appear long, nearly all the sites continue to play an important role in the attractiveness of the local scenery. The issues raised are predominantly about preservation of character in the long-term and survival of planted and built features.

In the following discussion of issues, the sites where the issue occurs is noted in brackets, although it may apply also to others. These references to sites may be omitted in the final report or if the summary report is to be made public, as this may be seen as critical of some owners.

More information on all of these issues can be found in the recently published Forestry Commission Scotland Practice Guide ‘Conserving and Managing Trees and Woodlands in Scotland’s Designed Landscapes’ available from FC Publications.

10.1 Conservation and management of planted features

Over mature and depleted parkland trees

Parkland adapted to golf course with new planting in character with the old

- Loss of individual trees and groups in parkland, or the over-maturity of such trees and their gradual decline, is a common feature due to age or some agricultural practices. Few areas of parkland have been comprehensive restocked with young trees, meaning there is a developing threat to this characteristic feature of designed landscapes given their ageing population.

- Parkland restocking normally can be planned using the 1st edition OS 1:2500 mapping, where available and is best approached using the original species. (Arden, Ardvorlich, Auchendennan, Benmore, Buchanan, Edinchip, Gart, Leny, Lomond Castle, Rednock, Shannochill, Stronvar)

- Woodland and tree belts are important features in nearly all designed landscapes and are the feature that contributes most to local scenery. Management, restructuring and restocking to ensure their long-term health, ecological diversity and survival may be required at some sites or a greater level of management may need to be encouraged. Generally the sites have not been assessed in any detail sufficient to recommend what management may be necessary, so sites mentioned are generally those where woodland and tree belts play a major role, or woodland management issues were recognised in some parts. (Arden, Auchendennan, Bannachra, Boturich, Buchanan, Finnich Malise, Gart, Invertrossachs, Shannochill, Stronvar, Stuckgowan, Westerton, Woodbank)

- Parkland within designed landscape has been attractive for the creation of golf courses for many years, ranging from older sites such as Buchanan Castle (laid out by James Braid in the 1930s) to large-scale leisure developments with hotel, chalets and golf courses in more recent decades. Planting within golf courses in parkland between fairways etc should maintain the character of the large forest trees traditionally used (oak, beech, lime, sycamore, Scots pine etc) but often small ornamental species are used (cherries, birch, rowans etc) (Buchanan, Drimsynie, Ross Priory, Rossdhu).

-

Use of appropriate forest species in parkland with other uses than golf, including native species in more areas of natural character. (Tigh Mor).

-

Several sites have gardens or landscape features that have been outstanding in their heyday but are now derelict or unmanaged. The Japanese-style water garden at Auchendennan and the Hill woodland garden at Edinchip stand out. Restoration has potential to make new visitor attractions, among other benefits. (Auchendennan, Edinchip, Glenfinart, Invertrossachs, Leny).

-

Care of specimen trees, including potential champion trees, veteran trees and tree collections. Small groups of special trees enhance many sites and give them individual character that is important to retain. (Arden, Ardvorlich, Buchanan, Drimsynie, Gart, Glenfinart, Inchmahome, Lomond castle) The emphasis here is on the less recognised sites rather than the well managed collections at Benmore, Balloch Castle, Ross Priory and Rossdhu.

-

Depleted designed landscape planting due to loss of tree belts, small woods and parkland trees creating grassland open to view and no containment for new buildings; restoration of the tree belts, field boundary trees and parkland trees should be encouraged. (Caldarvan).

-

New structure planting to integrate new development in the landscape, to help it relate better to its setting or if necessary screen intrusive features. (Drimsynie, Gart)

-

Avenue replanting / restocking can be problematic, whether to fell and replant, interplant or replant on a new line in order to conserve these impressive features. (Drumquhassle, Finnich Malise, Kinnell, Westerton).

-

Forestry in the wider setting completes the composition of many designed landscapes, as do loch views and other external scenery. The design of forests as seen from the core of the landscape is particularly important in these situations and an aspect that may be controlled by working in partnership with adjoining landowners and by recognition as an objective in forest plans. (Benmore, Buchanan)

Abandoned Hill garden at Edinchip

Specimen conifer group at Buchanan

Veteran sweet chestnut at Inchmahome

Planned view from Auchterderran house to Balloch castle

10.2 Visual issues

- The visibility of new features in the designed landscape and wider setting, particularly of caravans and chalets, is an issue at a number of sites. Landscape planting to help integrate and partially screen intrusive parts, while preserving views out, should to be encouraged. (Ardgarten, Glenfinart, Glenloin)

- Visibility of designed landscapes in cross loch views is a particular feature of the National Park and needs special attention when change through management or new development is planned. Marinas and other water’s edge development can be particularly problematic. In addition, some sites are intervisible with each other, placing even greater importance on the preserving or enhancing the quality of the view. (Ardgarten, Arden, Auchendennan, Buchanan, Boturich, Cameron House, Invertrossachs, Lomond Castle, Stronvar, Tigh Mor)

- The group value of sites at the south end of Loch Lomond and how they are seen ‘as one’ from across the water, and from the road or other viewpoints, also needs to be considered. (Arden, Auchendennan, Cameron House, Lomond Castle; Balloch, Boturich)

Image: Partially used walled garden at Ardvorlich

10.3 Division and dereliction

Derelict summer house

Shell of Woodbank house

Derelict walled garden at Glenfinart

Derelict stables block

- Divided ownership of sites almost invariably leads to a number of problems resulting from lack of coordinated management and applies both to some small and larger sites. Lack of overall responsibility for parts of the such places can result in neglected or derelict features, unmanaged woodland and tree belts, sporadic housing development, reversion to agriculture and proliferation of fences and signs, among other issues. (Arden, Auchendennan, Boturich, Buchanan, Glenfinart, Leny, Lomond castle, Stronvar)

- Derelict and neglected parts are a widespread issue and applies to at least twenty-six of the sites, and is perhaps an inevitable consequence of the economic and social changes since their creation in the 19th century.

- New uses for walled gardens is an issue across Scotland and applies to thirteen sites where the garden is uncultivated or derelict within the National Park. Encouragement for new uses is needed, particularly in some form of cultivation to make best use of the assets of soil and shelter, and it is heartening that community initiatives are planned in some cases. (Ardvorlich, Auchendennan, Dalnair, Glenfinart, Kinnell, Leny, Rednock – among others)

- A viable new use for the main house, whether underused, vacant or derelict, applies in a few cases and is potentially a future issue for others. (Balloch, Dalnair, Woodbank)

- A corollary of the previous point is the ambitious undertaking of private owners to restore houses, their gardens and designed landscapes which needs to be encouraged so that these places are conserved. (Camstraden, Duchray, Invertrossachs)

- Removal of intrusive buildings or uses may be possible when sites come up for redevelopment, giving the opportunity for more sustainable uses and improved design that is sensitive to the designed landscape setting. (Dalnair, Lomond castle)

10.4 Building use and built features

- Restoration and future use of unused or ruined buildings is a major issue complicated by the range of building types affected. These include stables/ estate office groups, gate-lodges, estate cottages, follies and summerhouses, glass-houses, boat-houses and ice-houses. Actions required may range from basic maintenance of the fabric to re-building and conversion to new uses. (Buchanan, Glenfinart, Leny, Stronvar, Stuckgowan, Woodbank – among others)

- Similarly other structures in the landscape need to be conserved including bridges, terrace walls and balustrades, gate-ways, family burial grounds and retaining structures. (Auchendennan, Buchanan, Kinnell, Leny, Lomond castle, Stronvar)

- Estate walls along roadsides are among the most visible features of sites and create a particularly poor impression if they become damaged or collapse, so their maintenance is essential. (Lomond castle, Woodbank)

- Repair and maintenance of estate fences along drives, estate gates, garden iron railings and balustrades, and other field enclosures. (Arden, Benmore, Dalnair, Finnich Malise, Gart, Kinnell, Leny, Rednock, Roman Camp, Woodbank – among others)

10.5 Other conservation and access issues

Collapsed roadside estate wall

Traditional iron estate fencing

- Opportunities to develop or formalise public access exist at several sites, or to improve existing provision or provide access to particular features. (Ardvorlich, Buchanan, Dalnair, Edinchip, Rednock, Stronvar)

- Surprisingly few sites are formally open to the public (Balloch, Benmore, Inchmahome), given their National Park location, although several others have fairly open access as hotels and golf/leisure development. Encouragement of formal opening, even if only to limited areas, may have benefits to owners including justifying restoration and promoting tourism.

- The issue of carrying capacity applies in some places receiving many visitors in fragile environments whether due to ecological sensitivity, archaeological features or the quality of the visitor experience. Design of surfaces may also need special attention in these situations. (Inchmahome)

- Management of vehicular circulation and control of vehicles on drives applies where there is a high level of mixed use including public pedestrian access. (Buchanan)

- Vandalism overall has not been noted as a prominent issue, although instances of damage to structures and setting fire to a garden building show that the problem is not entirely absent. (Auchendennan, Roman Camp)

- Nature conservation issues issue need to be balanced with designed landscape management at a number of sites with NNRs and SSSIs within or adjoining their boundaries, and in other cases where neglect has resulted in increase in nature conservation values. (Buchanan, Rednock, Rossdhu, Stronvar, Wards)

- Some sites have particular archaeological sensitivity and potentially archaeological values may need to be balanced with aims for designed landscape conservation. (Inchmahome, Rossdhu)

- Rhododendron control is a widespread issue and was noted in particular at some sites. (Arden, Auchendennan, Stuckgowan)

- Pests and diseases affecting particular types of trees and shrubs appear to be on the increase nationally, although generally not an issue that the survey was able to identify. The presence of Phytophthora was noted at two sites and the resulting damage to planting and expense of eradication was a concern. (Balloch, Ross Priory)

10.6 Issues in relation to development, development pressures generally

Image: Castle and leisure centre, Drimsynie

- Integration of sites of golf courses in designed landscapes; design in relation to parkland / woodland setting; types of planting recommended. (Buchanan Castle, Cameron House, Drimsynie, Ross Priory, Rossdhu)

-

Height and mass (ie. scale) and intensity of new built development within the National Park, its outstanding picturesque designed landscapes and the wider natural landscape setting. (Ardgarten, Cameron house, Lomond castle)

-

Appropriate siting and integration of caravan parks and chalet developments; mitigation of intrusion by planting. (Drimsynie, Lomond castle, Leny, Ardgarten, Gart, Glenloin, Glenfinart)

-

Marinas and water-edge development – particular visual issues where no screening is possible in views across the water; other aquatic environment issues. (Cameron house, Lomond castle)

-

Exemplar sites – examples of good practice, design and use of materials, grounds maintenance, new planting, conversion to new uses. (Balloch castle, Cameron House, Ross Priory, Tigh Mor)

-

Appropriate materials, hard and soft; fence divisions and design (Camstradden, Lomond castle)

-

Control and design coordination of signage; use of temporary signs. (Cameron house, Lomond castle, Stronvar)

-

Design and integration of car parking. (Balloch castle, Cameron house, Lomond castle, Rossdhu)

-

Development control, continuing development pressures, approved or pending development. (Buchanan, Glenloin, Leny, Lomond castle, Woodbank)

-

Temporary but intrusive buildings, as at wedding and events venues, ie. large white marquees etc. (Boturich, Cameron house)

-

Forestry planting; planting of parkland and other open ground in designed landscapes. (Shannochill)

-

Conservation Management Plans recommended as a basis for dealing with the issues arising at particular sites and to plan and coordinate future management and development. (Auchendennan, Boturich, Buchanan, Drimsynie, Invertrossachs, Leny, Rednock, Stronvar, Westerton)

Image: Core area of finely managed designed landscape in new use at Rossdhu.

11 Management recommendations – five potential project areas and priorities for designed landscape conservation

Restoration projects – projects to restore gardens, walled gardens and garden features at Auchendennan, Edinchip, Glenfinart, Invertrossachs and Leny.

Restock parkland planting – encourage restocking at Arden, Ardvorlich, Auchendennan, Benmore, Buchanan, Edinchip, Gart, Leny, Lomond Castle, Rednock, Shannochill, Stronvar, with Buchanan and Leny being the priority sites in terms of visibility and significance.

Rejuvenate and manage woods, tree belts and avenues – encourage the uptake of SRDP grants to rejuvenate and manage woods, tree belts and avenues within designed landscapes, targeting those sites lacking management and with deteriorating planted features.

Improve access – plan for public access to sites within the parameters of the Outdoor Access Code, making available traditional and old routes wherever possible, and encourage formal opening of places of interest.

Encourage suitable forms of development – support development where this will provide viable long-term new uses for designed landscapes and provide investment to conserve the deteriorating fabric. All development should be planned within the context of a Conservation Management Plan to ensure that potentially intrusive features are integrated by high quality design and planting and other environmental effects are mitigated.

12 Conclusion

The designed landscapes covered by this survey make a significant contribution to the landscape character of the in the National Park, through their policy tree features, woodlands, tree belts and tree-lined fields, their buildings and the natural topographic features on which they are based. As the previous paragraphs show, the sites vary greatly in their distribution, size, style, periods of development, features, current uses and condition.

The designed landscapes are distributed unevenly within the National Park – many located on lochsides, others sited by rivers, others in more secluded hill country. Some, such Ardvorlich, Benmore and Stronvar, stand in relative isolation resulting in a dramatic presence in the wider landscape. Around the south of Loch Lomond, where many sites have been congregated, the designed landscapes have group value, are the main influence on man-made landscape character, and their intervisibility gives them additional significance. Although the designed landscapes in the National Park have much in common, each one is made special by its location and the peculiar circumstances of its creation.

Several of the sites are in serious decline and few are without areas of neglect or other management problems. The report analyses the particular management issues associated with this type of landscape in the National Park and concludes with recommendations regarding priorities for their conservation.

The reports on individual sites should not be seen as comprehensive or conclusive but are aimed at giving a basic understanding of each place. All would benefit from more detailed historical research and ground survey. At the same time, the management recommendations will need to be developed into a strategy for action and the feasibility of individual projects examined in detail in consultation with owners and other stakeholders. By these means the important designed landscape component of the National Park landscape may be conserved for the future.

Appendix 1

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, a summary history of its designed landscapes, Christopher Dingwall.

Introduction

The designed landscapes to be found in any given area are a product of numerous factors, and the way in which these interact though time. On the one hand there needs to be some understanding of the physical geography of the area, embracing such things as geology, topography, soils and climate; on the other hand there needs to be an appreciation of the human influences, involving things such as the social status, political connections and economic circumstances of their creators; added to which there is the question of style or fashion which can be seen to change through time. While some designed landscapes are simple in their structure and character, and may be the product of a single creative period, many are complex and multi-layered, with long-established examples displaying features derived from several periods in their history. The process of change within such landscapes can be quite sudden, with major investment in planting and landscaping concentrated into a short time period, as with a change of ownership or the rebuilding a mansion house. In other landscapes, change is more gradual and subtle, as old landscape elements age and die, to be replaced by new ones. The follow is a summary of the main influences on designed landscapes in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park (the National Park) and an outline their history, illustrated with typical or outstanding examples of different styles and periods.

Physical framework

Within the National Park there is a considerable variation in topography, from the more subdued topography in the valleys of the Rivers Forth and Endrick, to the more mountainous landscapes of the Trossachs and the Cowal Peninsula.

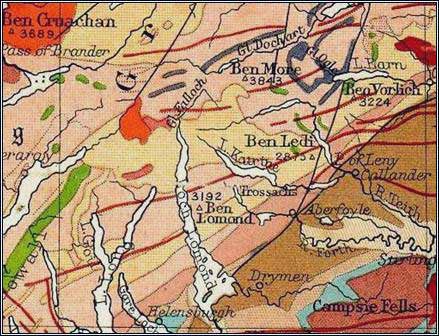

Image: Simplified Geological Map of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs

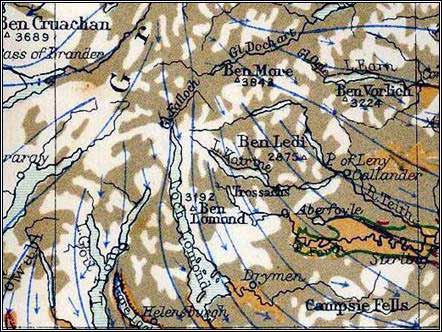

Image: Generalised pattern of ice movement during the last glacial period.

While the northern and eastern part of the National Park is characterised by freshwater lochs such as Loch Earn, Loch Venachar and the Lake of Menteith, the southern and western part includes the long sea-lochs of Loch Long and Loch Goil. Dividing the National Park almost in two is the huge expanse Loch Lomond, with its scatter of islands.

This variation in topography is in part a reflection of the underlying geology, with the Highland areas to the north and west underlain by harder metamorphic rocks, quartzites and mica schists of the Dalradian Series, dating from the Pre-Cambrian era; and the gentler Lowlands to the south and east underlain by the softer Old Red Sandstone rocks of the Devonian period. Running through the south-eastern part of the National Park from Callander in the north-east through Balmaha, to Arden in the south west is the great dividing line of the Highland Boundary Fault, though its influence on the landscape is less apparent than it is further to the north and east in Scotland’s Central Valley. Indeed, over substantial parts of the area the solid geology is obscured by later deposits.

One of the most important influences on landscape character has been the succession of glacial periods which has affected Scotland during the Pleistocene Epoch. The glaciers which flowed out from the Highland towards the south were responsible for breaching the natural watersheds and over-deepening preexisting river valleys which, now that they are filled with water, give us many of the area’s lakes. Unconsolidated deposits, whether moraine and boulder clay laid down directly by the ice, or fluvio-glacial sands and gravels laid down by meltwater streams derived from melting glaciers, have played a major part in determining landscape character in the east of the National Park. To the north and west are narrow glaciated valleys with less in the way of deposits to obscure the solid geology, except on the valley floors. A further influence in the west has been the rise in sea-level during the post-glacial, resulting in the drowning of the valleys and the creation of the western sea-lochs.

Landscape character and planting can be strongly influenced by soil type, generally shallower and more acid in upland areas, deeper and richer in lowland areas. Soils within the National Park vary from nutrient-poor peats and podsols in the upland areas, through forest soils, to the rich alluvial soils to be found in the valleys of the Forth and Endrick. Also important in its influence on patterns of settlement and planting is the micro-topography or landform, seen for example in the location of houses on rising ground to take advantage of views, in the siting of walled gardens on south and west facing slopes to maximise solar gain, or in the planting of trees for shelter from prevailing winds, or on steep slopes and rocky outcrops which cannot otherwise be cultivated.

Finally, there are climatic influences. Cloud cover and precipitation are significant factors, with some of the highest levels of rainfall in Scotland recorded over the Cowal peninsula and the Trossachs, rising to over 3,000mm in places, though falling to less than 2,000mm further east, in the shadow of the hills.

Mean temperatures, too, vary significantly, with proximity to the sea tending to raise minimum temperatures in winter, and lower maximum temperatures in the summer. Wind is yet another factor, with south-westerlies predominating.

Rainfall and temperature influence both the natural flora, and the range and type of exotic plants which can be grown successfully. For example, woodlands dominated by oak, ash and alder are more common than those made up of birch and Scots pine, an observation made by the Rev. James Robertson in his Statistical Account of Callander Parish (1794). It is the temperate maritime character of the climate which makes this part of Scotland so suitable for the growing of trees from the West Coast of North America, and which contributed to the choice of Benmore (35) as an outstation of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. However, these same climatic influences can also lead to problems, for example by encouraging the spread of invasive Rhododendron ponticum .

From earliest times to c1680

The physical landscape provided the framework within which prehistoric and later settlement took place, leading to the spread of agriculture and the exploitation of the natural forest. While other parts of Scotland became progressively denuded of trees, the value of the natural woods around Loch Lomond seems to have ensured their survival into medieval times. Although there is nothing to compare with the widespread influence of religious houses further to the south and east, early records tell, for example, of the use of timber from around Loch Lomond by the Cluniac house of Paisley Abbey, and for the building Glasgow Cathedral.

Further east was the Augustinian Priory of Inchmahome (33), established c1238.

Also significant was the formation and maintenance of hunting parks, for the recreation and enjoyment of royalty and the nobility, seen for example in the granting of a charter by James II in 1458 to John Colquhoun of Luss for the creation of one such park at Rossdhu (34).

Johan Blaeu’s map of Levinia or Dunbartonshire, based on manuscript maps compiled by Timothy Pont some 50 years earlier, and published in his Atlas Novus (1654), provides an overview of a broad sweep of country from Menteith in the east to Loch Long in the west, as it was around the turn of the 17th century. Although Blaeu does not indicate enclosed parks on this map, he does mark significant concentrations of trees around Buchanan Castle (38), Park of Drumquhassle (02) and Rossdhu (34). Planting at this time may have been influenced, at least in part, by government legislation such as that referred to by M.L Anderson in A History of Scottish Forestry (1967), which encouraged landowners to build ‘civil and comlie houses’ and to have ‘policie and planting about them’. Anderson also cites a lease of land at Tullichewan, in Luss Parish, dated 1636, which required the lessee to plant trees. At the same date, Camden’s account of the province of Lennox in his Britannia (1636) says of the shores of Loch Lomond that there be ‘…nothing else memorable, unless it be Kilmoronoc, a proper fine house on the east side of it, which hath a most pleasant prospect into the said lake’. Sadly, Blaeu’s Atlas Novus did not include detailed maps covering south-eastern Perthshire, the western part of Stirlingshire or the Cowal peninsula, so we do not have a comprehensive picture of the landscape at that time.

With the diminishing influence and final demise of the Earls of Lennox in the 17th century, other families came to dominate landownership in the area around Loch Lomond and the Trossachs – Buchanans and Grahams to the east of Loch Lomond, Colquhouns and Smolletts to the west, Argyll Campbells further to the west, Breadalbane Campbells and McNabs further to the north. As conflicts between clans and families diminished, wealth and prestige increased, leading to the aggrandisement of tower houses and to the creation of gardens and plantations.

From c1680 to c1780, period of enclosure and improvement

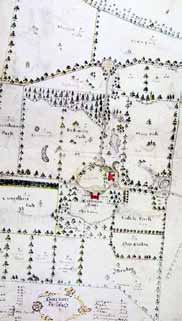

Images: Roy’s Military Survey of Scotland c.1750 showing landscapes at Buchanan Castle and Gartmore (National Library of Scotland / British Library)

The best record of the nature and extent of planting and landscaping prior to the mid-18th century is the Military Survey of Scotland (1747-1755) – commonly referred to as Roy’s Map after the Chief Surveyor William Roy – the first map to be drawn at a useful scale, and in a consistent style, comprehending the whole of the National Park. The first decades of the 18th century were characterised by the spread of enclosure and planting. For example, the year 1714, the first of King George I’s reign, saw the passage of An Act to Encourage the Planting of Timber Trees, Fruit Trees and Other Trees for Ornament, Shelter or Profit; the year 1723 was marked by the establishment of the Society of Improvers in the Knowledge of Agriculture in Scotland; and 1729 saw the publication by ‘a lover of his country’, understood to be William Mackintosh Laird of Borlum, of An Essay on ways and Means for Inclosing, Fallowing, Planting &c [in] Scotland.

As with the architecture of the period, the fashion of the time in landscaping was for regular enclosures and planting. Policy planting in the vicinity of the house was generally geometrical in character, with rectilinear ‘wilderness’ plantations cut through with straight rides framing vistas, or planted in the form of ‘rondpoints’ with several rides radiating from a central point – all intended to bring a sense of order to a previously unstructured rural landscape, and to emphasise the power and influence which the laird was able exert over his estate. Most notable among the large-scale landscapes of this type within the National Park were those of Buchanan (38) and Gartmore (25). We are indebted to Alexander

Graham of Duchray (fl.1700-1730) for his accounts of parishes in the vicinity of Loch Lomond in the 1720s, that for Buchanan describing ‘very handsome enclosures with very regular planting and policy’ (1724), and that for Gartmore describing ‘new inclosures and a great deal of young planting’. Smaller-scale examples of the regular planting of this period are to be seen at places such as Duchray (12), Kinnell (36) and Ross Priory (04).

A reading of the parish descriptions to be found in the [Old] Statistical Account of Scotland (1791-1799) reveals the considerable extent of woodland in the vicinity of Loch Lomond at this time, when compared with some other parts of Scotland, where deforestation had resulted in a landscape almost devoid of trees. What is also apparent from these descriptions is that few of these woodlands were being allowed to grow to maturity, as most were subject to coppicing on a more or less regular basis, a regime which saw them cut at intervals of c20-25 years.

Exploitation of the woods was aided by the proximity of the woods to lakes and rivers which provided a means of transport. The Rev. Dugal McDougal’s comments on the woodland in Lochgoilhead and Kilmorich Parish (1792) are of particular interest for the light which they shed on the state of woodlands at the time. As he observed ‘timber has become so scarce and so valuable that in a considerable part of such a country as this, the woods yield a greater profit than anything else which the lands can produce. The natural woods, therefore, are now regularly cut and preserved with care ; and there is a great number of trees planted yearly in different places. The natural woods consist of ash, alder, hazel and birch, but mostly oak ; and there are several plantations… of Scots and silver fir, larix, elm, beech, plane and lime’. Likewise, the Rev.

David MacGibbon says of the Parish of Buchanan (1793) ‘Near the House of Buchanan there is an old oak wood, to which great additions have been made within these 40 years past … From the Grampian Hills to the north end of the parish, along the side of the loch, is one continued wood, consisting of some ashes, alders, hazels, but mostly oaks. Woods are of late become very valuable on the sides of Loch Lomond, as the timber and bark are easily transported to Glasgow, Port Glasgow and Greenock, and sometimes are carried to Ireland and the West of England’. This impression of a fairly well-wooded landscape is further strengthened by a sketch of Strathleven and Loch Lomond made by Paul Sandby, the principal draughtsman of Roy’s Military Survey, c1747, which depicts woodland stretching some way up the surrounding hillsides from the shores of Loch Lomond.

From c1780 to c1880, period of development and consolidation

From the late 18th century onwards, we begin to see changes, both in the nature of landownership, and in the style of landscaping. While some estates were passing from one generation of the same family to the next, others began to reflect the growing influence of Glasgow on its hinterland, and of the extraordinary wealth generated by its industries and trading links. We see the dominance of ancestral piles begin to be challenged by the ostentatious ‘castles’ of the nouveaux riches, made ever more accessible for their aspiring owners by improvements in the road network, by the arrival of the railways, and by steam powered boats – a process of colonisation described by Michael Davis in his chapter on ‘The Villas of Scotland’s Western Seaboard’ in Dana Arnold’s book The Georgian Villa (1996) and by J. Mordaunt Crook in his book The Rise of the Nouveaux Riches (1999), in which part of Chapter 5 is devoted to ‘Scotland, New Money in the Highlands and Islands’. Throughout this period, we also witness the rapid development of tourism.

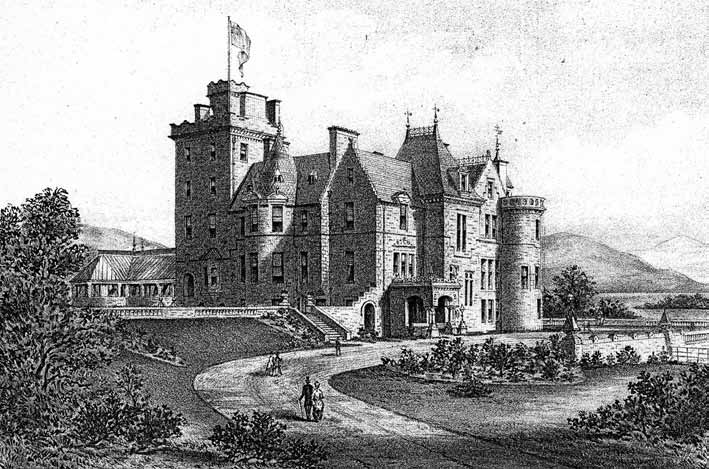

Many of the new houses eschewed the classicism which had characterised earlier houses such as Rossdhu (34), for the newly-fashionable Scottish baronial style of architecture. With this came a new fashion in landscaping, more akin to the English ‘parkland’ style associated with Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, where the house looked out over pastoral scenery ; where woods were no longer straight-edged and regimented, but rather boasted sinuous edges ; and where tree-studded parkland and curving drives supplanted the rectangular parks and straight avenues of earlier times. In this style the model gentleman’s estate is seen to be embraced by plantations, its boundaries defended by walls and gate lodges. Within this boundary are sweeping carriage drives which lead to the front of the house, while more functional service drives give access to working features such as the court of offices, the walled garden and the service wing of the house, without the need for working traffic to pass in front of the house. The house is often seen to be placed on rising ground to take maximum advantage of views over its park and the surrounding scenery.

During this period, estates such as Rossdhu (34) which can be seen to continue under the ownership and management of successive generations of the same family become the exception rather than the rule. Instead we see the reflection of new wealth in houses and their associated landscapes such as Balloch Castle (09) built for Glasgow merchant and banker John Buchanan in 1809; as Auchendennan (07) built for tobacco baron George Martin in 1865; as Arden House (06), built for publisher Sir John Lumsden, Lord Provost of Glasgow.

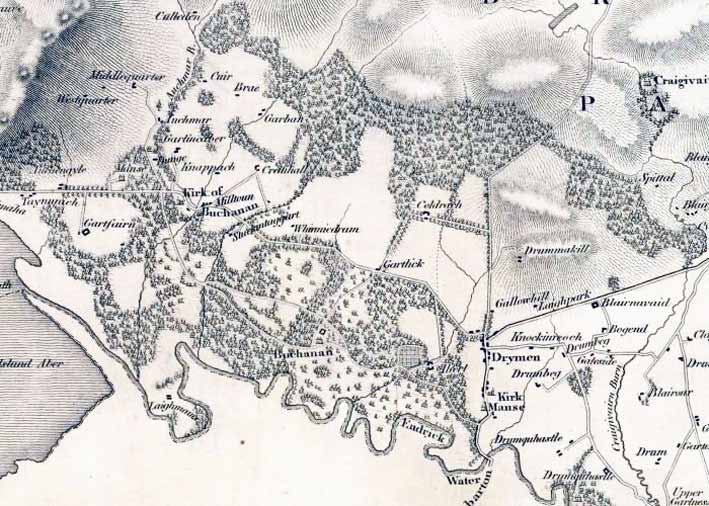

Image: Policies of Buchanan Castle J. Grassom’s Map of the County of Stirling, 1817 (National Library of Scotland)

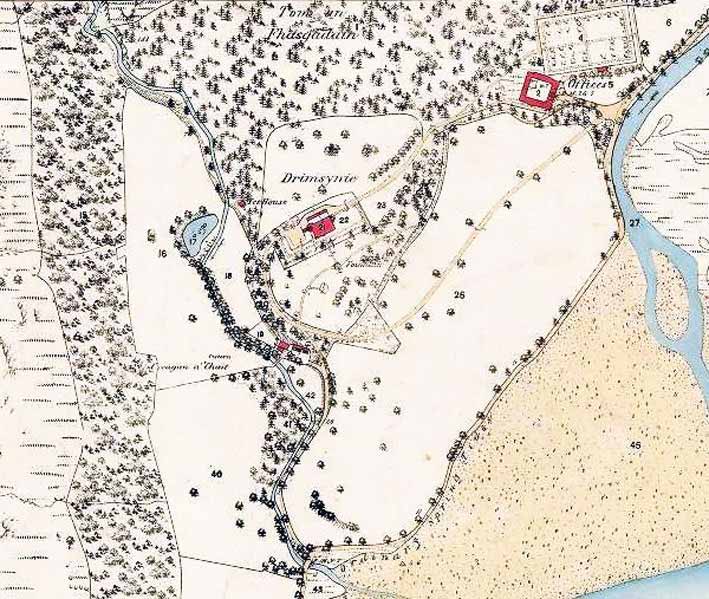

Image: Drimsynie House and policies, 1st edition Ordnance Survey 1:2,500, 1866 (National Library of Scotland)

Nor was this pattern of change confined to the shores of Loch Lomond. To the west we see, for example, Drimsynie (03) acquired by Liverpool merchant Ronald Livingstone, who replaced an earlier house with the present castellated mansion c1860; or Benmore (35), partly built by James Duncan on the proceeds of the sugar trade, and further developed and aggrandised from the 1880s by the Younger family on the back of their brewing business. To the east is Rednock House (37) developed c1827 for Major General Graham Stirling around an earlier house, and Stronvar (29) built in 1850 for banker and industrialist David Carnegie.

Image: Auchendennan House, from The Book of Dumbartonshire by J. Irving 1879 (RCAHMS)

To date, there are only two or three places where it been possible to identify the landscape designer involved in preparing layout plans for an estate – namely Rossdhu (34), for which the English designer Thomas White (Sen.), one-time associate of Lancelot Brown, prepared a plan in 1797; and Cameron House (14) for which his son Thomas White (Jun.) is recorded as having prepared a plan in 1819. It can be supposed that, as architect of the fantastical pile of the Trossachs Hotel – now Tigh Mor (23) – and of the neighbouring Brig o’Turk Parish Church, George Penrose Kennedy and/or his father Lewis Kennedy, who had been responsible for remodelling the gardens at Drummond Castle in the 1830s, may have played an active part in the creation of the surrounding landscape. The role of Charles Ross at Gartmore 1781 – whether as surveyor or designer – is less clear, without the benefit of additional research. Where they have survived the passage of time, the plans and papers relating to other estates covered by this survey have yet to be explored. Nor is it clear, without further research, to what extent the landscapes for which plans were prepared may have been influenced by the designs commissioned by their owners.

Image: Plan of ‘Gartmore Inclosures’ by Charles Ross, 1781 (National Library of Scotland / SCRAN)

Many of the aforementioned gardens and landscapes were in their heyday towards the end of the 19th century, boosted by income from trade and industry, and employing large numbers of people on comparatively low wages. Yet the somewhat temporary nature of landownership is seen in the number of times that some properties changed hands, for example Benmore (35) which had six different owners in the space of 60 years between 1830 and 1890. This was a trend commented on earlier by the Rev. M Mackay in his New Statistical Account of Scotland for the Parish of Dunoon and Kilmun (c1840) where he observed that ‘while building and other improvements proceed actively, numerous families of tradesmen from the town on the Clyde, and labourers, reside for a year or two and then remove. Landed property also has undergone several transfers since the period of the last Statistical Account. It is believed that there are only two estates in the parish similarly situated as at that period, all the others having undergone transfer, diminution or change’.

It should be remembered that some properties were retained as hunting lodges, to be used by the family at certain times of year, while others were let to tenants on a more or less permanent basis. Thus, in The Sportsmen’s and Tourist’s Guide to Scotland for 1880 Ardgartan (08), Ardvorlich (05), Camstradden (10), Duchray (12), Edinample (24), Edinchip (16), Gartmore (25), Leny (32), Park of Drumquhassle (02) and Stuckgowan (20) were all recorded as being occupied by tenants, rather than the properties’ owners.

From 1880 to the present, period of change and fragmentation

Image: Undated photograph of Benmore House, Argyll (Newsquest / SCRAN)

Image: View of Balloch Castle in the 1960s by J.Valentine (St. Andrews University / SCRAN)

Although most of the aforementioned landscapes would have entered the 20th century well-managed and in comparatively good shape, and a few such as Gartmore (25), Invertrossachs (18) and Roman Camp (30) even saw new investment in building and garden making at the start of the century, few estates were left untouched by the dramatic social and economic changes which occurred in the wake of the two World Wars. Subsequently, in a part of the country with an established tourist trade, several of the area’s country houses such as Auchenheglish (31), Cameron House (14), Drimsynie (03), Glenfinart House (15), Roman Camp (30) and Woodbank House (28) were converted to hotels, while other properties such as Ardgartan (08), Auchendennan (07) and Stronvar (29) became Youth Hostels. In other cases, as at Buchanan (38), Drimsynie (03), Leny House (32), Invertrossachs (18) and Stronvar (29) parts of the estate woodland were sold to the Forestry Commission at different times, and now serve as part of one of the area’s two Forest Parks – Argyll Forest Park on the Cowal Peninsula, and Queen Elizabeth Forest Park in and around the Trossachs. Benmore (35), gifted to the nation by the H.G. Younger in 1925, was first conceived as a ‘National Arboretum’ for Scotland to be managed by the Forestry Commission, but responsibility for its management soon became divided between the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, in whose ownership the gardens now serve with Logan and Dawyck as one of three outstations ; and Forestry Commission who continue to manage most of the surrounding woodland as part of the Argyll Forest Park. The Balloch Castle (09) estate, easily accessible from the city by road and rail, was acquired by Glasgow City Council in 1915 and is now leased to West Dunbartonshire Council, under whose management it continues to serve as a County Park. The demand for holidays and recreation has also seen several designed landscapes fall victim to the demand for caravan sites and chalet developments, as at Drimsynie (03), Glenfinart House (15) and Glenloin House (21) in the west; at Cameron House (14) and Lomond Castle (31) on the western shore of Loch Lomond; and at Gart (17) in the east. Two of the areas most important landscapes now harbour golf courses – that at Buchanan Castle (35) being laid out to a plan by celebrated golf course designer James Braid as long ago as 1936, that at Rossdhu (34) the work of Tom Weiskopf and Jay Morrish in the 1990s. Two more golf courses have been developed within the grounds of Cameron House Hotel (14).

Some houses have become institutionalised, as at Gartmore (25), most recently reborn as a conference and activity centre, where the landownership is now fragmented; and at Ross Priory (04) where house and grounds retain their integrity – different scenarios which have predictable consequences for the character and integrity of their designed landscapes.

As elsewhere in Scotland, some houses have fallen into ruin, or been partly or wholly demolished. While all trace of the house at Ardgarten (08) has gone, the unroofed shell of Buchanan Castle (35) still survives, surrounded by 20th century residential development; only a small part of Glenfinart House (15), the greater part of which was destroyed by fire in 1968, survives amongst a sea of caravans; and the fate of Woodbank House (28), burned in 1997, remains uncertain more than ten years on, as its landscape continues to decay. In the case of Ardgarten (08) a large newly-built hotel is destined to become the focus of a remodelled landscape.

Amidst all of this change are a number of houses and estates which remain in private ownership, and continue to be managed in a traditional way, such as Ardvorlich (05), Boturich Castle (01), Camstradden (10), Edinample (24), Invertrossachs, (18), Kinnell (36) and Rednock House (37).

Conclusion

The designed landscapes in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park which are the subject of this report make a significant contribution to overall landscape character, through their buildings, policy woodlands, surrounding plantations and tree-lined fields. As the main report shows, the sites are distributed unevenly within the National Park. Some, such Benmore (35), Stronvar (29) and Ardvorlich (05) stand in relative isolation resulting in a dramatic presence in the wider landscape. Around the south of Loch Lomond, where many sites have been congregated, the designed landscapes have group value and their intervisibility gives them additional significance.

Although the designed landscapes in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park have much in common, and can be categorised according to their period, style or other characteristics, each one is made special by its location and the peculiar circumstances of its creation. This broad-brush historical account was undertaken to inform the wider survey of sites and should not be seen as comprehensive or conclusive, but rather as the start of the process of unravelling the complex history of designed landscapes in the National Park and as a basis for future and more focused research.

Peter McGowan Associates

Landscape Architects and Heritage Management Consultants

6 Duncan Street Edinburgh EH9 1SZ

0131 662 1313 • pma@ednet.co.uk

March 2012

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park

Historic Designed Landscapes Project

Summary Report