Killin Heritage Trail

Grading: easy.

Killin is at the heart of Breadalbane – the beautiful ‘High Country’ of Alba, ancient kingdom of Scotland. This is also where two powerful rivers – the Dochart and the Lochay – flow beside the village and join beyond it. The Killin Heritage Trail is easy to follow, mostly along the line of Main Street and Manse Road. If you like, you could take a longer loop to make a circuit, or use the village as a base for exploring the wider land, woods and waters of Breadalbane. There are way-marked routes, opportunities to hire bikes, canoes and other sports equipment.

At a glance

- Grading: easy

- Distance: 1-2 miles

- Path type: pavements and firm-surfaced paths

- Allow ½ to 1 hour

The old village square at the eastern end of the village

Villagers have been familiar with the ring of the Killin and Ardeonaig Parish Church bell since the 17th century. The bell was cast in 1632 by Robert Hog, one of a family of bell-founders based in Edinburgh and Stirling. A neat ‘birdcage belfry’ perches at the top of the eight-sided structure which is the church’s oldest part. This was built in 1744, and extensions, including the rectangular section with the main door, were added in the 1830s. The ancient Healing Stones of St. Fillan are now located in the church. By tradition the layer of river wrack on which the stones are bedded is changed every Christmas Eve.

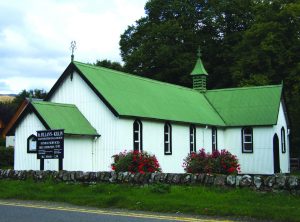

The small, white-and-green painted Episcopal Church (St Fillan’s) is made from corrugated-iron sections erected in 1876, using money from Gavin Campbell, 7th Earl of Breadalbane. Nicknamed ‘The Grouse Church’, it was once used by guests on the Earl’s private shooting parties. These days, it is open to all and was recently restored to help preserve it. The Campbells of Glenorchy were once the most powerful clan branch in Breadalbane and beyond, with lands from Argyll to Kenmore. Chiefs became barons and earls. Their castles included Kilchurn, Taymouth, Edinample and (just north of Killin) Finlarig. Now an unsafe ruin, Finlarig hosted a Scottish Parliament meeting at a time of Civil War in 1651. But only three members attended.

Killin has long had links to Gaelic language, certainly back to when St. Fillan – an Irish, Gaelic-speaking priest – settled here in the 8th century. In the late 1800s, more than four in five Killin folk spoke Scottish Gaelic. They would have benefited from the work of the Rev. James Stewart (Stuart), minister of the Church of Scotland. In 1767, he was the first person to translate the whole of the New Testament into Scottish Gaelic. There’s a monument to him outside the church.

|

|

| Aerial view of Killin | St. Fillan’s Church |

The Main Street and Park Entrance

Some houses in Killin almost literally grew from the surrounding fields and rivers. These include some of the oldest in the village, like the single-storey row of cottages across the road, which could date from the 1700s.

Here, as in many parts of Scotland, early buildings were made from the most readily accessible local stone. Some of it didn’t even need to be quarried. The beds and rocky sides of the two rivers that flank the village were a source of both rounded and flatter stones. Rocks cleared from fields could also be changed from a nuisance to ploughmen to a boon for house building.

Go through the impressive gates of Breadalbane Park and follow the path to the lone rock that rises from the turf. Called ‘Fingal’s Stone’, this recalls a time when, it is said, a band of warrior heroes – the Fianna – roamed the hills and glens of Scotland and northern Ireland. Some think that their leader, Fionn mac Cumhaill (pronounced ‘Finn Macool’ and modified to ‘Fingal’ by a popular 18th-century writer) lies buried here. Fionn had many adventures, including with his hunting dog, Bran.

Main Street to Manse Road

For much of the last few hundred years, Killin was a thriving trading point and an important place for the manufacture of textiles. Its location at the foot of three glens, beside a river crossing and near a military road from Stirling to Fort William, helped people to reach it. Good farmland and woods provided food and fuel around it, while the rivers powered watermills for weaving cloth. Villagers earned a living through various trades, such as supplying the needs of farmers and labourers who came to the six fairs held here every year.

Branch line and new trade routes

A big change to this pattern came in 1886, when the Killin branch line of the Callander to Oban Railway opened. Killin Station was located where the car park is now, at the north end of the village. A mile from Killin the railway reached Loch Tay Station. In the early years of the railway a wooden pier was built to serve the steamboats that provided a regular service on Loch Tay and rails were installed to enable boats to load or unload at the station. The railway provided an easy means of moving sheep and cattle, as well as other goods. Thousands of tourists came to the village on the special round tours, and cheap day tickets, from Edinburgh and Glasgow.

It was in this period when many of the owners of big new houses moved out in summer and used the cottages at the rear, so that the main house could be let as holiday accommodation. It was a very different lifestyle from that lived in the past by the weavers, shoemakers, stonemasons, tailors, blacksmiths and flax workers who were typical inhabitants of village cottages in the 18th century. The Loch Tay station closed to passengers in 1939, and the railway closed entirely in 1965.

|

|

| Gray Street | Water Mill |

Manse Road and Main Street to Monemore

Turn up the slope off Main Street to see Manse Road. One of the first buildings there has a square-sided insert, high on its wall. ‘Freemasons’ meet here, in what was once ‘Sawmill Cottage’. Freemasonry is a non-religious brotherhood with deep roots in Scotland (Robert Burns was a freemason) and a worldwide membership. Some of its symbols – such as the square and compasses carved here – are based on stonemasons’ tools.

Further up Manse Road, the first large house on the right is the one that gives the road its name. This was built by the 1st Marquis of Breadalbane to house a rebellious, but locally popular, minister. He was one of hundreds of preachers who had left the Church of Scotland in the 1840s to form the Free Church of Scotland after a bitter dispute about how ministers should be appointed.

A little farther on, Pearl Cottage was once the home of fishers who took freshwater pearls from the River Dochart. Freshwater mussels have long gone from here and most of the other Scottish rivers where they once thrived.

Falls of Dochart, Bridge and Innis Buidhe

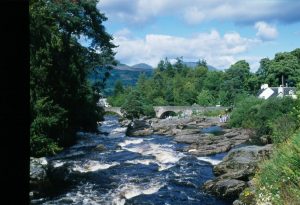

Back on Main Street, walk along to the bus drop-off area at Monemore and continue to the old mill and the bridge at the Falls of Dochart.

Small, but powerful, the Dochart river is fed by burns that tumble from Breadalbane’s hills. Issuing from Loch Dochart, it merges with the Lochay downstream of the village, not far from where the combined flow enters Loch Tay. Its name could mean ‘Scourer of Evil’, suggesting a pure and cleansing force.

St. Fillan built a meal-grinding mill here in the 8th century. The mill that now stands near the Falls was built around 1840 and tweed was woven in it until 1939. Both the mill and the bridge are made almost entirely of local stone, much of which could have come from the river itself. The same applies to the Falls of Dochart Inn and the row of old, single-storey cottages on Gray Street, across the river from the mill.

Just downstream of the bridge is ‘Innis Buidhe’ – The Yellow Island – which is the ancient burial ground of the Macnabs. Killin was once at the heart of Clan Macnab territory, which stretched from Tyndrum to Loch Tay. The clan name comes from ‘Mac an Aba’, meaning ‘son of the abbot’, with members claiming descent from an Abbot of Glendochart. Both geography and associations to a saint of the early Celtic church – Fillan – would make this an ideal last resting place for Macnab chiefs.

|

|

| Falls of Dochart | The Main Street with Perthshire’s bens in the background |

Download walking route and map

This information was created by a partnership between Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, Historic Environment Scotland, Stirling Council & Killin Heritage Society

Text: Kenny Taylor, Natural Media

Photographs: Caitlin, Jack, Nathan and Sophie from Killin Primary School, David Mitchell, Euan Myles, Kenny Taylor, Killin Heritage Society, National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Wildlife Trust, Sheila Winstone